Like me, you may have heard of a few of these far away places but aside from some cursory knowledge, countries in the South Pacific might also be buried in blurry or basic details. The cool thing with experiential knowledge is how it brings life to textbook tales. Located between NZ and Hawaii, the Kingdom of Tonga consists of 36 habitable islands within a total of 172 islands, all of which are all divided into four groups.

Throughout Oceania, it amazed me that humans, habitats and homes that were far flung from one another somehow seemed to get the memo on shared customs and traditions. In an ever changing world with latest trends, I wondered how foundational pillars are upheld across time, tides … and TikTok.

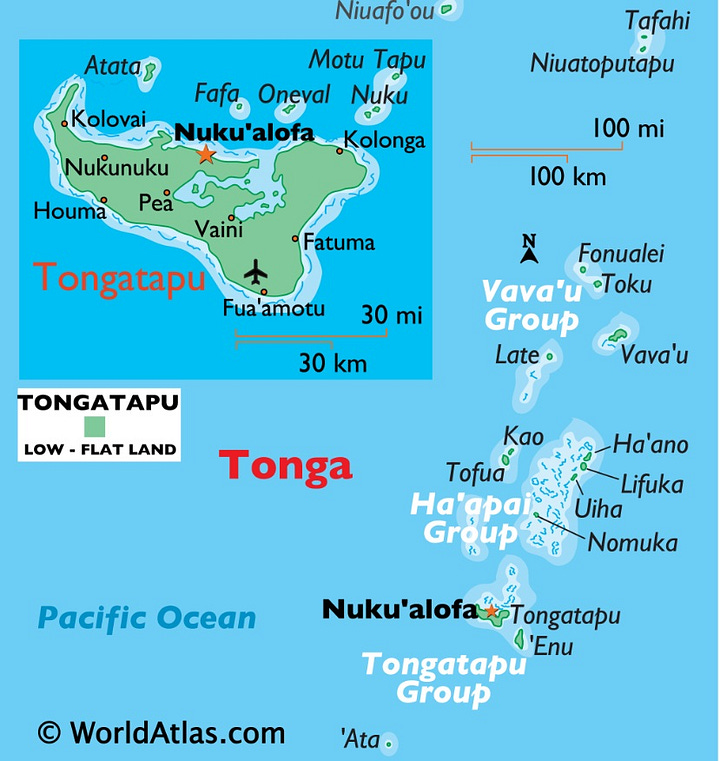

Orienting the islands can be helpful. At the south end is Tongatapu Group which houses one of two international airports and is home to the Nuku’alofa, the capital and largest city. Some smaller islands such as ‘Eua is accessible by a “concise seven minute flight” (or 3 hour ferry!) though all flight options were ‘on hold for the next bit’. North of this cluster is the Ha’apai Group which includes 51 islands, of which 17 are habitable and apparently, is home to beaches worth boasting about. Continuing northerly is the Vava’u Group of 50 islands, which includes Hunga Island - a famous place where humpback whales gather, though there are several sighting spots in the country. At the northerly tip is the isolated Niuas Group where tenting is the only option since no actual accommodation exists given the lack of international tourism there.

Named as the ‘friendly islands’ by James Cook, the anga faka-Tonga (Tongan way) rooted itself in aka'apa'apa (respect), talangofua (obedience), fakaongoongo (waiting and listening for instructions), and 'ofa (reciprocal sharing and helping). I was fortunate to learn of these familiar facets and other traditions when Lea, a 71 year old Tongan wandered my way.

I was sitting on a picnic bench, watching a kid’s birthday party in the background. A quarantined section of water at Tongatapu’s harbourfront served as an outdoor haven for folks to splash, trash and splunk into. For the festivities, a blown up Spider-Man undulated in the wind, making it seem that he too was dancing the day away.

Lea was waiting for his son, the DJ for the event, and was pleased to engage. When I later met Mele, the only female taxi driver on my entire South Pacific tour and Soana, the sole deaf person I encountered, they too added some pearls and perspectives.

Like cousins, several countries in the South Pacific share similar customs, social norms and the religion of Christianity. Sundays therefore, also remain a day where much of the country’s services shut down. The quantity and quality of religious infrastructure was evident, quickly outnumbering business shacks and services. A myriad array of churches lined the lanes, lapsing only a little between each of them. How quickly one can see what people value …

There are several displays of respect that have been passed down through the generations. Lea shared that they were taught not to eat their father’s leftovers or to sleep in his bed, all as a sign of respect. Within a family, the eldest sister ranks high and it is customary to fulfill her wishes, even if that were to include taking and raising a younger sister’s newborn, though Mele shared that if and when this happens, both parties are usually in agreement, stating ‘no one can force them’. In spite of her hearing impairment, Soana shared that suboptimal situations exist where folks face domestic violence and burdens of mental health that surfaces in family life. To that end, several sign posts encouraged speaking out against violence, presumably as an attempt to make it less of a taboo topic in today’s times.

As I look to recent global events, leadership and country and communal values, I wondered how respect for others (and ourselves) is inculcated and transmitted. How can each of us nudge our lives towards tolerance, togetherness and inclusive traditions?

Seeing sacredness in nearby Samoa, it seems that strong ties to the past have carried on customs to the present for some countries and communities more so than others. Rooting back to their ancestors, the wearing of woven ‘blankets’ called ta’ovala serves as a reminder said Lea, that even in olden days, Tongans were ‘covered and didn’t roam naked’. Now a sign for respect, ta’ovala are worn in the presence of royalty, at funerals, church and sometimes at school. Generally woven by the wife, each ta’ovala can take two weeks to weave, though they can also be purchased in some cases for approximately $50 USD. On landing at the airport, I was privy to witness Nicholas receiving a blanket by his loved ones.

Getting a glimpse like this into Tongan culture was as special as it was serendipitous and Lea was open to sharing on so many fronts. He mentioned that similar to other world cultures where gender is not viewed as binary, a ‘third gender’ referred to as fakaleitī (like a girl) is found here in Tonga. From his perspective, Lea felt many chose the role themselves and that parents are less likely to designate, though it seemed to be part of a similar tradition where families with only sons could select one son to dress and act as to uphold the ‘duties of a daughter’. Lea suggested that since same sex intimacy was illegal, most of the fakaleitī would marry women and could have their own children. Fakaleitī being male at birth, could inherit land from their fathers, though women were never recipients of such estates.

How do we respond when worldviews sway from the normative and does this tether or abdicate what we hold dear, I wondered.

In Tonga, much of the past lingers into the present. As a monarchy, land belongs to the King. Lea explained that 20 to 30 nobles ‘fall under the King’ and thus, aside from royal properties, Tonga was piecemealed and given to these nobles. Their duty in turn was to divide up the land amongst the male family heads. This land could not be sold by nobles or others, but can be leased. Upon a passing, the eldest son would alert the village noble to replace the father’s name with theirs. In the case where a man had no children or only daughters, the eldest brother would be heir to the land, deciding its use ‘without question or conflict’. Hearing this, my emotions oscillated - the grip of patriarchal structures juxtaposed with the circumvention of family dramas over deeds and dollars. When I chatted with Mele later on in the Uber, she felt that times were shifting and squabbles over property are, unfortunately, becoming more common.

Assigning of land rights in Tonga seemed to have a process. Given the devastation of property near Ha’atafu beach on the western side of Tongatapu, the King had offered villagers an alternative plot of land. Lea shared that even though many Tongans were grateful for this generous offer since one could only own one plot (approximately eight acres, of which half would be farm land), most villagers opted to stay where they and their families have lived for generations, in spite the ongoing risk of natural disasters.

Fortunately, the impact was limited in lives lost. Regardless, it seems that cemeteries punctuate the labyrinth of main and accessory roads, akin to several islands in the South Pacific. In Tonga, nobles dictate which land should be designated for this purpose and assign slabs to each family. To ensure appropriate decomposition, a gap of five years is required for spouses to share the same tomb. Elaborate headstones, some with plastic flowers, blankets, flashing lights and even large posters and photos mark each person’s grave. Driving by several, I noted flocks of families coming to pay respects and refurbish their family’s shrines. In fact, in the immigration line I met Tanya, a graphic designer who, along with her engineer brother, run a tombstone business - she’d mentioned that business was booming.

I was grateful to have spent some time with my new Tongan mates, each of whom shared their insights into the folklore, frameworks and functions that’ve been familiar to them. Prior to the advent of social media’s efficiency in spread, these communities have found ways to maintain many of their foundations. As I journeyed through these far away regions, I wondered what were the signature sections within my own world and how often we scan or study those elements that are worth safeguarding and showcasing.

May we be mindful of that which lays and strengthens our individual and communal foundations,